Introduction

When you think of the word "elephant," you may picture the world's largest land animal. When you hear "bird," you may think of something little and fast enough to fly. However, when you put those two words together, you get the "elephant bird," — a creature that seems almost impossible.

That bizarre pair was indeed a real creature. The elephant bird was no delicate songbird but a flightless giant that used to roam the island of Madagascar. Weighing as much as a baby elephant, they laid eggs large enough for an entire family to share. And in a few short centuries of human presence on its island home, it vanished entirely. How could something so enormous disappear so quickly? In this article, we'll explore the life, legend, and legacy of this remarkable creature— the elephant bird.

By Monnier – Digimorph.org, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Naming the Giant

The name "elephant bird" isn't just about its size, though that's certainly a significant factor. Early European visitors to Madagascar heard locals sharing stories about enormous flightless birds. These tales likely resembled the Mythical Roc from the Arabian Nights. These creatures were known to be strong enough to lift an elephant. Sailors, in need of a juicy tale, spread this sensationalized nickname, and it stuck.

Scientific classification provides one more layer. This colossal bird belonged to the extinct order †Aepyornithiformes and family Aepyornithida. However, some researchers prefer the less extensive family Mullerornithidae. There are three main genera of giant birds recognized by scientists: Aepyornis, Mullerornis, and the huge Vorombe.

Image Source:

- Aepyornis maximus: By Acrocynus, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Mullerornis modestus: By DFoidl, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed by CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Vorombe titan

The Aepyornis genus comes from the Greek words aipys ("tall") and ornis ("bird"). Mullerornis is named after the French explorer Georges Müller. Vorombe means "big bird" in Malagasy. Historical records also mention "vouropatra" or "vorompatra," which means "bird of the open spaces."

Each of these names provides insight into how different cultures perceived and remembered this giant. Names, however, only say so much. To really understand this bird, we need to look at their physical characteristic that made it so iconic.

Appearance and Anatomy

Imagine a bird as tall as a basketball hoop and heavy as a small car. Genetic studies show it was most closely related to New Zealand’s kiwi, though its body had evolved on a vastly different and gigantic scale. That is the elephant bird. The largest known member, Vorombe titan, measured more than three meters from the tip of its toes to the crown of its head. They also weighed about 650 kilograms.

Elephant birds were built for power rather than speed. Their legs were thick and strong, supporting their immense weight on the forested terrain of Madagascar. Their torso was barrel-chested, as if designed to store energy for long periods of foraging. Their short, powerful necks supported a head that was small compared to such a massive body.

These birds were flightless. Their wings had greatly diminished over millions of years to almost decorative appendages. Their powerful, clawed feet kept them rooted to the ground as they ate, and their strong. Also, their thick beaks were capable of cracking hard seeds. Even their bone structure showcases their adaptation as immovable but slow-moving giants, perfectly adapted to Madagascar's unique environments.

A Lost World: Madagascar Then and Now

If you were to travel back in time 1,200 years, Madagascar would be a very different place. The sea air on the coast carried the scent of the Indian Ocean. In contrast, the interior carried the scent of moist earth and flowering palms among dense forests. In this diverse habitat lived the elephant birds. These large, flightless birds navigated all types of terrains with ease.

These birds were not particular about their surroundings. They played a crucial role in the ecosystem by swallowing seeds whole and dispersing them throughout the island. Eventually, this subtle seed dispersal helped shape the Madagascar we have come to know.

Daily Life of a Giant

The elephant bird was the unchallenged sovereign of Madagascar's forests and plains. Species, such as Aepyornis maximus and Mullerornis modestus, ate leaves and fruits from low shrubs and trees. Aepyornis hildebrandti enjoyed grazing on grasslands and foraging in forests. Their diet consisted of rainforest fruits with thick shells and giant palm nuts. They swallowed these seeds whole and scattered the seeds as they moved through the island. These birds had poor eyesight and relied on their acute sense of smell to find food.

Palm nuts Photo by Zdeněk Macháček on Unsplash

Love, Eggs, and Family Life

Elephant birds likely timed their breeding to coincide with the rainy season. This season is when fruiting peaks occur, and the food is available for both adults and chicks. The courtship rituals were likely subtle, similar to those of contemporary ratites. There were no elaborate displays or vocalizations. They preferred bonded close contact and quiet posturing.

Their nests were shallow, broad ground scrapes that were located on open areas free from flooding. The eggs were the largest of any bird. They were heavy and thick-shelled, requiring careful handling during laying. The fossil record suggests that these giants made no effort to cover each clutch, so guarding was crucial.

Parenting likely resembled that of ostriches and emus—the closest living relatives of the elephant bird. A single parent, possibly the male, takes on the responsibilities of incubation and guarding. They used their powerful legs to deliver a bone-crushing kick to discourage predators from coming near. Chicks hatched fully feathered and able to walk, learning in a matter of hours. They quickly learned how to forage and stayed close to the protective shadow of their giant parents.

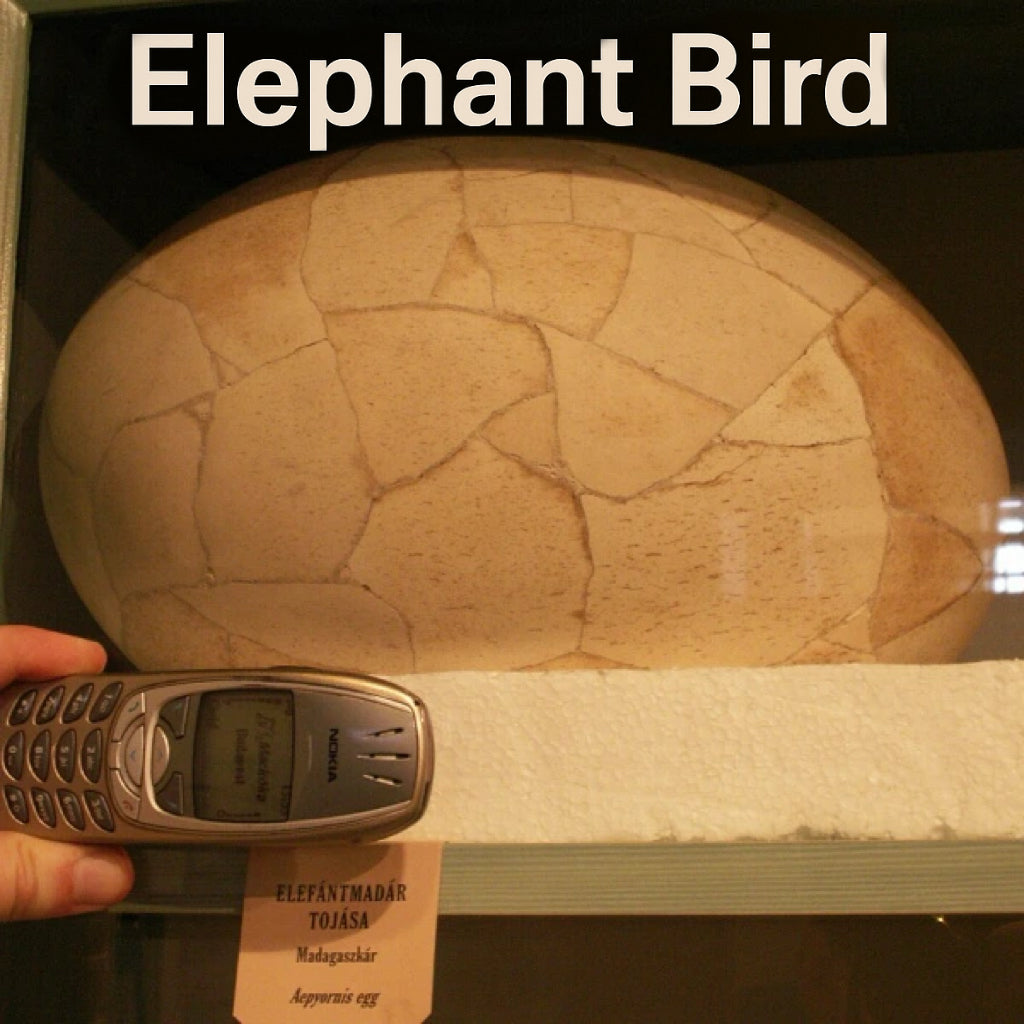

The Egg That Defied Belief

We've already touched on the elephant bird's size, but its egg is one of its most extraordinary traits. Measuring up to 40 centimeters long, weighing around 10.5 kilograms. It could hold up to 5.6 to 13 liters of content, making it more than 160 times the volume of a chicken egg.

The shell was equally remarkable. The Aepyornis eggs measured approximately 3.3 millimeters thick, while the Mullerornis eggs were almost 1.1 millimeters. The thickness allowed the eggs to withstand the weight of a sitting bird. But it's still delicate for a chick to crack when it is fully grown.

To humans, these eggs were no novelties. In Madagascar, fragments were used in daily life and painted red with motifs designed to repel evil spirits. It was said that a single egg could feed a whole family. Victorian collectors bought intact shells and sold them for profit. In contrast, others were donated to museums.

Elephant bird egg (far left, 1) and chicken egg (third from right, 6)

By Denis Bourez, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed by CC BY 2.0.

What Science Has Uncovered

The extinction of the elephant bird was not a sudden event. This extinction was a gradual decline that began with the arrival of humans in Madagascar. As humans burned areas for pastureland, they disrupted the delicate habitats of the birds. Lowland breeding grounds were lost, and even in the highlands, Aepyornis hildebrandti faced threats. Monster eggs, each weighing as much as a dozen ostrich eggs, were taken for food. Additionally, the disease introduced by domesticated birds may have spread through the elephant bird population.

Why the Elephant Bird Still Matters

We may not be able to revive the elephant bird, but we can still preserve the birds we have now. In Madagascar, elephant birds once carried huge seeds in their bodies and dispersed them across the island. Without them, many plants that produce fruit suffered. The seeds of these plants are too large for small birds to handle. Today, Australian and New Guinean cassowaries, ostriches, and emus perform the same role. If we lose these birds, entire forest ecosystems could collapse.

Modern research shows that conserving large, flightless birds such as cassowaries and emus is critical for seed dispersal and forest regeneration, and by saving today’s giants, we can ensure a greener world for the future.

Conclusion

The loss of the elephant bird shows the tremendous effect of the loss of a keystone species on an entire ecosystem. Though we can never bring back the elephant birds, we can preserve their living relatives, such as cassowaries, emus, and ostriches. Preserving these species allows us to keep forests healthy and the necessary natural processes intact. The message is stark: We must do something today to make sure the giants of today don't suffer the same fate as Madagascar's lost giant.

FAQs About the Elephant Bird

When and why did the elephant bird go extinct?

Elephant birds went extinct in Madagascar 500 to 1,000 years ago due to human activities. Habitat destruction, diseases, hunting, and high-intensity egg collecting were some of the primary causes.

How big was the elephant bird compared to other birds?

Aepyornis maximus, the largest of its kind, stood 3 meters high and weighed up to 500 kilograms. Their eggs were the largest on record.

What did the elephant bird eat?

They were primarily herbivores, and their diet consisted of fruits, seeds, and leaves.

How much is an elephant bird egg worth today?

Complete or nearly intact elephant bird eggs can sell for $30,000–$100,000 at auction, depending on condition, completeness, and provenance. Partial shells are also valuable, typically selling for a few thousand dollars.

Is an elephant bird an ostrich?

Aepyornis maximus, the elephant bird. The elephant bird and kiwi belong to a group of birds called the ratites. These include the ostrich from Africa, the rhea from South America, the emu and cassowary from Australia, and the extinct moas of New Zealand.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.